'Poetic justice': Somali diplomat in Tehran reflects on Iran in the run up to the revolution

Somali diplomat based in Iran from 1976 reflects on the country, its people and crucially its pre-revolutionary political atmosphere

We usually stumble upon the diary accounts, books and memoirs of western diplomats. Many of them tend to go onto glittering careers commenting on the country (or countries) they were based in for established think tanks which makes their work and ideas more accessible to us all. There are a variety of reasons for this, from the ability to keep archives and open them to the public, to the freedom granted individuals to comment on matters like that; but I also think this has a lot to do with the way power and knowledge produce and reproduce one another. I’m somewhat guilty of that as so far many of my sources have been American. But I suppose this post flips that on its head.

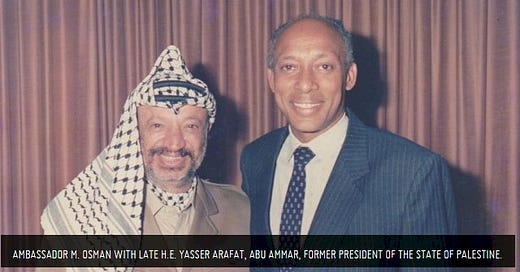

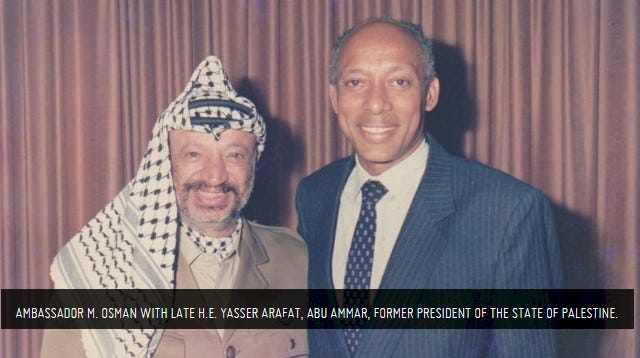

In this case we have a Somali diplomat–Mohamed Osman Omar–who moved to Tehran in 1976 to establish a Somali mission to Iran. Prior the Ogaden War which marked a turning point in Somalia’s ties with US allies in the Middle East, I don’t have any evidence to suggest that Mogadishu and Tehran had any issues in their bilateral ties. However, when Somalia cut ties with the USSR during the war, Iran enthusiastically embraced Somalia even committing to its defence if Ethiopian troops crossed the Somali frontier. In March 1978, the New York Times reported that a senior Iranian official said “Iran would go to the defense of Somalia if the Ethiopians and Cubans were so unwise as to push across its borders.”

Omar arrives in Tehran slightly ahead of all that. The city resonates with him on profound religious and cultural levels; and Iran more broadly bears many similarities to his own in terms of the asymmetries which colour their respective ties with their superpower patrons. Like many Iranians, Somalis were on a similar quest for broader and more meaningful independence, which offered the masses greater say in the decisions determined the conditions of their lives.

Omar’s sojourn in Tehran coincides with a pivotal juncture in Iran’s history, with the spectre of an imminent “Islamic Revolution” looming large; though he doesn’t put his finger right on it, Omar was definitely aware that the moment was pregnant with equal measures of transformative but also destructive potential. Omar doesn’t draw clear parallels between the conditions of both countries, but his thoughts assume a heightened significance for me because Somalia was undergoing its own radical metamorphosis into a authoritarian militarised, socialist state around the time he was in Tehran. He bitterly complains for example about the fact that he had to sing a song praising Somali leader Siad Barre every week describing it as “bizarre” and “stupid.”

Both countries tackled the critical question of how to reclaim sovereignty and agency in the Cold War in very different ways. In 1979, Iran mined the abundant reservoirs of its cultural and religious inheritance to reimagine a collection of concepts and symbols that would serve as powerful catalysts for the revolution; whilst Somalia relied on Marxist ideas which it indigenised and hybridised to serve its own needs. Somalia looked to Moscow and Beijing, whilst Iran chose to go its own way by conjuring up a call buried deep in the bowels of its history.

A decade separates the transformative events which shaped the trajectories of these two countries. Whilst Somalia’s 1969 coup led to state collapse in 1991 when the curtains fell on the Cold War reducing its strategic value, many who still spend their time predicting the fall of the Ayatollahs–mainly Americans it has to be said–have consistently found themselves confounded by the regime’s remarkable resilience.

Omar’s account is fascinating for those reasons. But like any dutiful socialist, he’s also a keen observer of the poverty stricken slums of Tehran’s south and how that contrasts with the extravagant lives of city’s nouveau riche. In an unexpected twist as well, Omar was shocked when in the month of Ramadan he was invited to an exhibition organised by the government during the day in which drinks were served. He expressed his thoughts to a protocol officer, informing him that it was Ramadan and that people were meant to fast. Whilst the officer explained that non-Muslims were present, Omar doubled down on his view, insisting that they should “respect our religious prescriptions.” “As a Muslim myself I felt very strongly about this,” he wrote. Throughout his reflection on life in Tehran you get the idea that this is why he sympathised with Iran’s marginalised masses, which he said were generally more observant of their faith and cultural traditions compared to the elite circles in which he moved.

Omar paints a portrait of a neglectfully decadent but also dangerously authoritarian and paranoid regime to whom he raised human rights concerns regarding the activities of Iran’s feared SAVAK. In the end the Iranians accused Omar of being a Russian spy on account of what “I had been reporting about the authorities, the system, the opposition, and the Secret Service in Iran.” The Iranians informed the government in Mogadishu but Omar was relieved to find Mogadishu “was on my side.” Giving a pithy summary of that entire episode he writes:

“Like Iran, Somalia was ruled by a dictatorial regime, and they had expected I would be punished in the same way that their own dictator dealt with his people.”

In the final analysis he says, the Shah “never thought that the wealth he had accumulated belonged to the people. Instead, he deposited hundreds of millions of dollars in US banks.” It was a kind of “poetic justice”, he continues, “when he was refused entry to that country after he was compelled to flee his homeland in the wake of the popular Islamic revolution of Khomeini.”

For all those reasons and some more that you are likely to discover, I think Omar’s account makes for a great read. His book, The Road to Zero: Somalia’s Self-Destruction, can be bought here.

Note: I chose to remove the more general and pedestrian remarks he made about other issues in this chapter. Namely, his concerns about Ethiopia’s ties with Moscow as it underwent its own Marxist revolution and what they would mean for Mogadishu. I think they are worthy of a separate post though and will line that up.

Until 1976, Somalia did not have a resident Mission in Iran. In June 1976, I was sent to Tehran as Charge d’Affaires to establish our embassy, pending the appointment of an ambassador. The Government of Iran was showing deep sympathy and concern for our problems with our neighbours and the uneasy relations developing with the Soviet Union. The Iranian Foreign Minister, Abbas Ali Khaladbari had recently visited Somalia to express his country’s support for us. Since relations between Iran and the United States were very friendly then, and Iran sympathized with our problem, we presumed that Iranian overtures of support might have the approval of the Americans. In the middle of the conflict in the Horn of Africa between Somalia and Ethiopia, in which Ethiopia was supported by the Soviet Union and its allies, I felt I should attempt to find out if the Americans actually were on our side. I knew an American diplomat in Tehran. On several occasions we had exchanged ideas on the contemporary situation in Iran and its neighbouring countries. Our discussions had ranged widely, and we had talked about alleged human rights violations in Iran, the rumoured brutal activities of the SAVAK (the Security Service of Iran), and the activities of the opposition group against the regime of Shahan Shah Arya Mehr, Mohamed Raza Pahlavi.

...

Despite the enormous income from its oil revenues, the majority of Iran’s population was extremely poor. In the southern part of the capital, the people lived in a very miserable condition. In some parts of the city, one could not drive a new car, certainly not a Mercedez or a luxury car, for fear of being attacked by angry poor people. From time to time I went to Jaaleh Square, the capital’s poorest area. I always parked my car at a distant place, and I never went there wearing a tie. A large number of people in Iran lived simply on bread, cottage cheese and mint leaves. Only the upper class and middle class could afford good food at restaurants. The rich lived in the northern part of the city, which appeared a different world altogether. The Shah lived at his Niavaran Palace, apparently unconcerned or unaware of conditions in his country. Was it that those who surrounded him always informed him that the people were happy, that everything was going smoothly in the country, and that all was well with his Takhte Taawoos—his Peacock Throne?

The millions of dollars he got from oil exports were invested in armaments. The members of his family led a luxurious life. Their children were educated in Switzerland, and the masses were left to struggle for survival. In the rich neighbourhoods of the northern part of the capital, the wealthy class enjoyed an extravagant life. Dinner parties started with caviar and boiled Caspian Sea shrimps and ended with belly dancers.

Islam was supposed to be the religion of the country, in fact only the poorer section of the population had anything to do with religion. It was the poor who visited mosques to offer their prayers. Once, during the month of Ramadan, the Government of Iran organized an exhibition of old secret documents of the State. At the opening ceremony, which was presided over by a member of the Royal Family, drinks were served. This was in the morning, at about 10:10 o’clock. I expressed my surprise to the protocol officer, that food and drink were being served during the day in a Muslim country when the people were supposed to be fasting.

As ours was a small embassy, we employed only five local hands: a secretary, a typist cum telephone operator, a driver, a messenger and a watchman. As in many countries of the world, I knew that the local staff would either voluntarily go to the secret service to offer their services or otherwise the service agents would approach them as soon as it was known they were employed at an embassy.

The Iranian Secret Service, SAVAK, were in the habit of listening in to embassies’ telephones. Sometimes, they would dial the embassies or the residences of diplomats, male and female, and mouth obscenities. This was extremely annoying and sometimes distressing. Yet, if the embassies reported this to the police, no action was ever taken to apprehend the delinquents.

I occupied some rooms on the top floor of the Chancery building. The flat below was occupied by the Secretary of the Embassy. One evening, when the telephone rang, I picked up the receiver—after office hours the telephone was connected to my apartment, and also had a parallel line to the room of the messenger. I heard the voice of the messenger who had picked up the receiver just before me. I kept silent and put my hand over the mouthpiece, so that he would not detect my breathing or the vacuum in the line.

The call was for him. The caller sounded authoritative. He told the messenger to come down to the petrol station that was situated at the end of our road. They spoke Persian and I understood the gist of their conversation. As soon as the receiver was put down I rushed to the balcony window of my flat, from where I could see the gates of the Chancery. I turned off the light before looking through a slit in the curtain, for he would have been able to see me had he looked up. The messenger came down to the gate, opened and shut it very quietly. I could see him clearly. He was in a great hurry, putting on his jacket while rushing to his rendezvous.

As soon as he moved out of sight I went out to the gate and locked it from the inside, so that the keys he had with him would not open it. I collect his clothes and belongings from his room and handed them to him when he returned. “You can come tomorrow morning for your wages,” I told him, and did not allow him back on to the premises that night. The messenger had been hired by us only recently, on the recommendation of a person we knew. His superiors should have waited a while, at least until he was well settled in the embassy, before trying to make use of his services.

...

Despite the little irritations that the Secret Service caused the diplomatic missions, including ours, relations between Somalia and Iran were very good, and the Iranian Government gave strong moral support to the Somali cause.

In the midst of the high tension in the Horn of Africa, where the struggle for the liberation of the Ogaden had escalated into war between the Somalis and Ethiopians, the President of the United States of America, Jimmy Carter came on an official visit to Iran. A formidable section of the Western media was on our side jut then. Since the media in the West has a reputation for influencing public opinion, as well as moulding the mind of their leaders, we thought President Carter should have some sympathy for the Somali position.

Moreover, since the Horn of Africa was a current flash point in world events, it must have been on the agenda for his discussions with the Iranian Monarch. Soon after President Carter had left Tehran, one of the Iranian national dailies carried a report titled: ‘Whoever harms Somalia will be considered as harming Iran’. In other words Somalia’s enemy was the enemy of Iran. We were very happy at this turn of events as it seemed that President Carter and the Shah of Iran had indeed discussed our problems during their meeting, and agreed to support Somalia. I could not persuade myself to believe that the press report was a mere coincidence, as in those days the press in Iran was tightly controlled and could not publish anything that did not have the Government’s blessing. Added to this, the Government of Iran always consulted their US friends before taking any initiative in foreign affairs.

A few days later, a high ranking Iranian Army Officer confided to us in the embassy that Iran was indeed preparing to send some assistance to Somalia. He also implied that Iran was waiting for approval from the White House for the assistance to be airlifted to Mogadishu.

...

The Iranian Officer was to keep in touch with me. Several days passed, and I began getting a little anxious about the delay. If they, USA and Iran, had agreed to help us, what was taking so long? Our expectations had been raised by the Iranian promise of assistance, following the US President’s visit. We could not imagine that there would be any hold ups.

Yet, all our hopes and expectations were dashed to the ground when the American Ambassador to Iran, Mr. Sullivan informed us that White House had objected to the Iranian offer of assistance. For a moment we were stunned by the statement of the US Ambassador. We did not react. It was not for us to ask why. The USA did what it considered best for its own national interests. But, keeping in mind the fact that Somalia was fighting the Ethiopians, who had embraced communism, and that the new communist regime there had expelled all Americans from its soil, and that the Russians and their allies—all enemies of the United States and the West—were openly supporting Ethiopia, we were unable to understand the negative response of the Americans. Somalia had freed itself from Soviet influence, and the US could have filled the vacuum and re-established its influence in the region.

...

At the Ministry I met with the Director General for consultations about my past and my future posting. He told me that the Iranians had accused me of being a Russian spy. The Iranians had accused me of this in a letter sent through their embassy in Mogadishu. The Director General, the senior most officer after the Minister, also informed me that the Ministry was of the opinion that the allegation was in reaction to what I had been reporting about the authorities, the system, the opposition, and the Secret Service in Iran, and therefore, he said “we believe that they must have been opening our diplomatic pouch before passing it to the airlines."

...

When I was told about the Iranian allegation against me, I was not at all surprised. Like Iran, Somalia was ruled by a dictatorial regime, and they had expected I would be punished in the same way that their own dictator dealt with his people. But this time the revolutionary government was on my side.

Throughout the period when I was in Iran, Shah Mohamed Reza Pahlavi’s regime was torturing and killing innocent people. Had the Shah utilized national resources for the common good, with the oil revenues of a single month, he could have built an apartment for each of his 35 million citizens. Yet, the majority of his people neither had adequate nourishment nor a place of shelter. Anyone who visited Jaaleh Square in Tehran could foresee the impending doom of the Shah’s regime. The tolerance of the common people suffering abject poverty on the one hand, against the glittering lifestyle of the rich was bound to reach bursting point.

The Shah’s advisors who presented a rosy picture of the dismal conditions of his people were his real enemies. But so too were his foreign friends (or masters) who considered themselves champions of human rights. They never gave him sincere advice, much less condemn the rampant violations of basic and fundamental rights to life and existence.

The Shah himself never thought that the wealth he had accumulated belonged to the people. Instead, he deposited hundreds of millions of dollars in US banks. It was surely some kind of poetic justice when he was refused entry to that country after he was compelled to flee his homeland in the wake of the popular Islamic revolution of Khomeini. His friends denied him the opportunity to spend his last days in peace in their midst, or even a place to die. He followed his own father’s destiny, who had died in an asylum and was buried in South Africa. Thanks to the late Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, the Shah was allowed to land in Cairo and at his death to be buried there.

During my stay in Tehran, I was privileged to enjoy the friendship of many common people. I visited their homes and they also came to see me at my place. These Iranian friends would frequently tell me that a man at the gate had tried to stop them entering, or had asked them their names. I had no guard at the gate, and I worried for their safety.

In spite of the seemingly water tight power of the Government, the Opposition was very strong in Tehran. This was reflected in the fact that there were open attacks from time to time against foreigners of countries that supported the Shah’s regime, and the Ambassador of a country which was a powerful ally of the Shah did not dare fly the national flag on his car, but preferred to travel incognito. He was protected by armed guards and sharp-shooters.

This Ambassador drove to cocktails with two or three similar cars as cover, so that it was not known in which car he was travelling.

The Government called the opposition who were operating within the country, Islamic Marxists.