The role of sports in the Somali revolution

The revolutionary government identified sport as one of the key tools to bring about the "complete transformation of Somalia"

This week, I came across a pamphlet published by the Somali government’s information and national guidance ministry in 1974, outlining the various ways in which the socialist government of Siad Barre aimed to reshape the country in its image. It is titled, “The Revolutionary Generation of Tomorrow: Youth, Sports and Manpower”. “The Glorious October Revolution aims at nothing short of the complete transformation of Somalia economically, socially, politically, and culturally, in the shortest possible time,” it reads.

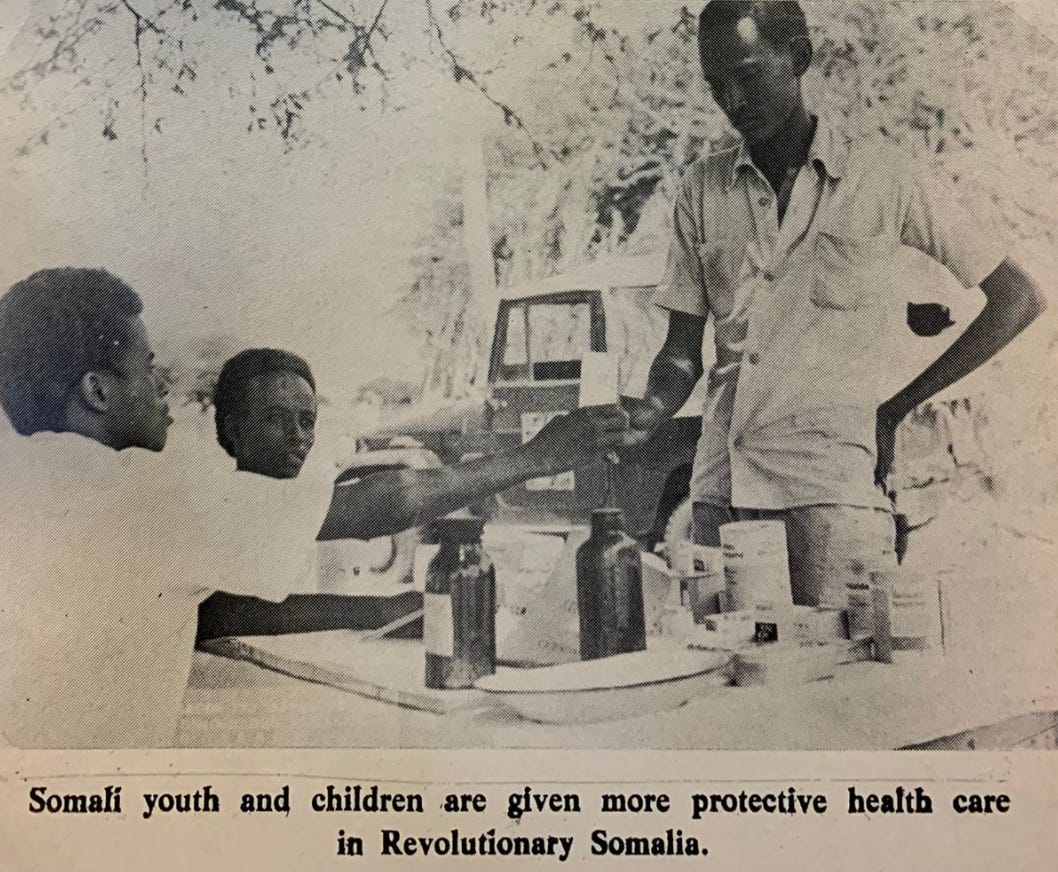

The type of Somali citizen depicted as the ideal by the regime through its programs is described as follows: “Revolutionary Somalia firmly believes in the fact that man, and man alone, is the central agent in nature and the environment. Consequently, by educating, re-orientating, and re-motivating the people in the right direction, as well as by channeling all the available resources of the country toward the attainment of our national objectives, we are bound to achieve this seemingly impossible task.”

More specifically, the author, Ismail Ali Abokor, secretary of state for information [aka propaganda chief], specifies the following as their goals:

to instil a higher sense of nationalism and patriotism in the mind of our youth

to cleanse them of all the residues of the past such as individualism, tribalism and other social evils

to give them plenty of opportunities to meet their age groups in various social context in order to foster mutual understanding and to develop their sense of leadership

to provide them with unlimited opportunities for useful and pragmatic education of scientific and of a cultural nature.

This text screams dictatorship vibes. It's a Siad Barre parade who stars throughout as the '“Father of the Nation”, with each chapter kicking off with his quotes as if he’s the all-knowing sage with otherworldly insights. Here is one example in the chapter on the importance of catering to the youth were he is quoted as saying: “It is needless to say that no society that neglects its youth, its future leaders, can expect to survive.” The chapter on the “Victory Pioneers” concerningly opens like this: “There is no difference, at all, between the forces which used to oppose our struggle for independence and those who oppose socialism today. Both of them aim at and work against the common interest of the Somali people. The Somali people, however, will crush the forces of reaction and will bury them as well.” Doesn’t sound to me like different views on development were getting much airtime.

There are other parts which I quite liked. Especially the emphasis on preparing young people to take control of their lives and the general direction of their societies and their country. The following passage on building a civic ethos focussed on social justice was interesting:

“At each stage of its development, society demands on the individual, regarding his professional training, general cultural level, political and moral make-up. Education and training must give the young people about to enter social life the right kind of orientation, and mould him into an active fighter for social justice. This presupposes his emotional and intellectual assimilation of the general ideals and principles of Socialism. It is important that the young man is given a scientifically substantiated picture of the future. A clear vision of the future will give rise to creative initiative and enthusiasm, promote the young person’s social awareness, and make him confident that his destiny, no different from that of millions of others, is in his own hands.”

Perhaps that goal succeeded and that led to the groundswell of opposition in the late 1980s to his dictatorship?

I can’t provide all the details of the text here, but I believe you grasp the overall vibe. The Somali government aimed for citizens dedicated to the ideals of Scientific Socialism and who discarded ancient social ills like tribalism. It believed that manipulating nature to serve society was the ultimate goal and was ready to take drastic measures against anyone proposing alternative ideas.

My favourite section, however, delved into sports, which is full of cool photos. The sports chapter opens with the epithet: “Sharp minds are in healthy bodies,” by guess who? The government considered sports as an “integral part” of Somalis’ nomadic lives before urbanisation in the latter half of the twentieth century. “Hunting, long-distance walks, and horse riding were routine practices for nomads in search of wild game or green pastures for their livestock,” it reads.

The colonial governments in Somalia are credited with introducing Western sports like football, basketball, and tennis to specific societal groups and constructing infrastructure for these activities. However, little effort was made to propagate them to the broader Somali public. The initial post-independence governments are doubly blamed for failing in that regard:

“One corrupt civilian regime followed another and after 9 years of independence all sporting competitions in the whole country were limited to a four-team soccer tournament and poorly organised, ill-lit nocturnal basketball games concentrated in Mogadishu.”

The author complains that the failure to invest in sport meant “hundreds of talents had to spend their leisure time sitting at tea shops watching cars roll by. And almost the same four teams played in every football competition until the birth of the revolution.”

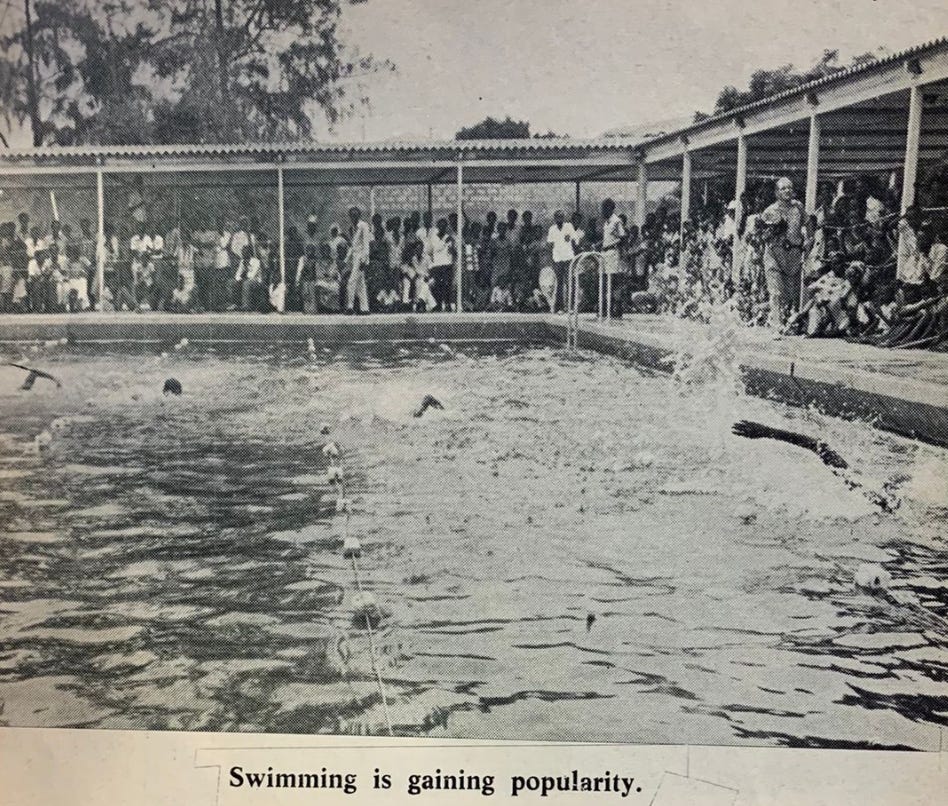

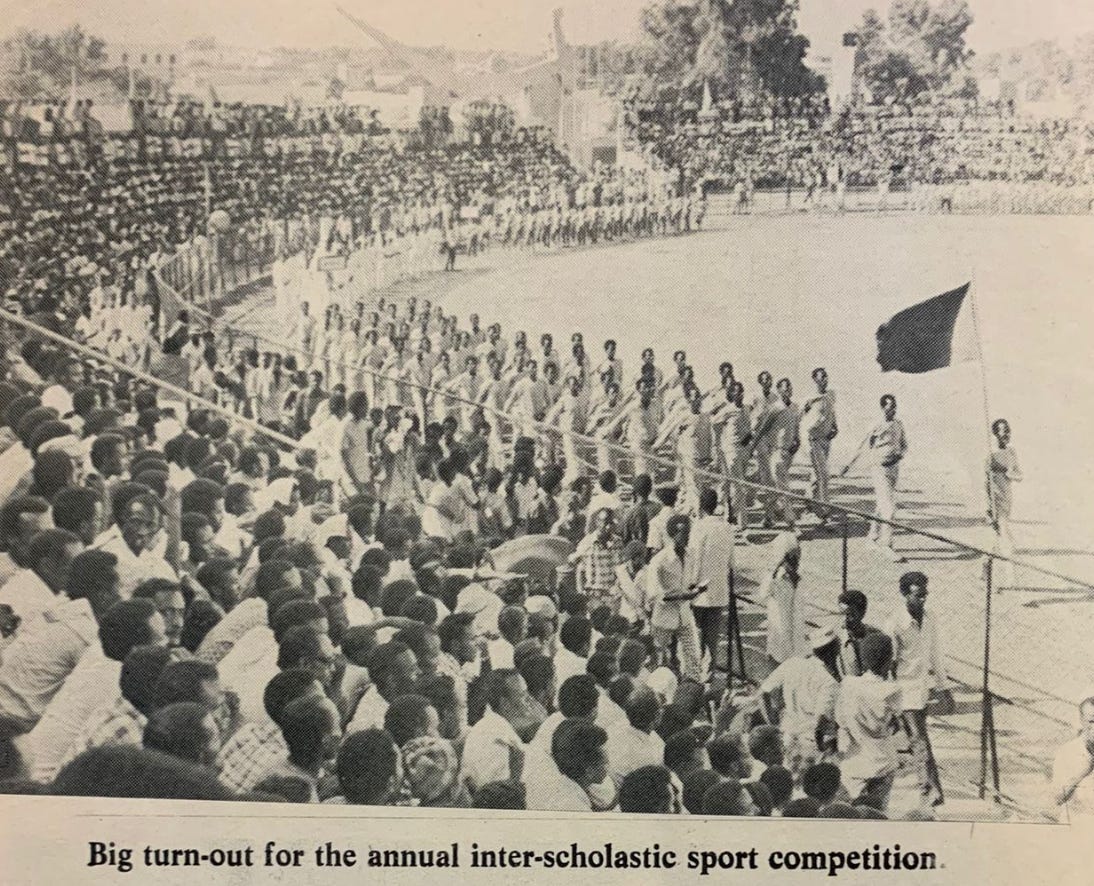

Since then the government boasts the following. The 21st October sports centre opened with full floodlights for basketball with an olympic standard swimming pool attached. A National Tennis Club was opened. The National Soccer Division went from four to ten teams, and at the time of writing had 24 teams competing. The Basketball Federation had more female teams than male, with 25 competing in the capital Mogadishu alone. And a Somali National Olympic Committee was established in 1970 that “covers all the associations and federations of different sports… even the most remote areas of the country.” The regime was determined to instil an appreciation for sport in the public:

“We are doing everything possible to put in the minds of younger generations the value of sports. Our youngsters are not inferior to those winning honours in international games. They lack neither the ability, the desire nor the competitive spirit. The only obstacle was that they had never been given the opportunity to prove themselves before the inception of the Revolution.”

It had some success too apparently. The pamphlet celebrates the success of Abdulle Wasuge, who won three gold medals East African Games and went onto come first in the high jump at the All-Africa Games in Lagos.

Somali women were also provided new opportunities to make their names in sport – having previously had to endure “hostile stares” – through the government’s programs and went onto represent the country at the Afro-Asian Ping Pong Championships in Peking (Beijing). Here are some photos of sporting events in Somalia from the early half of the 1970s: